Blue Like The Color Of Distance

On Rebecca Solnit, getting closer, Yves Klein, and a snippet of soon-to-be-published flash fiction

Like sickness, fascination often takes hold of a person slowly before spreading rapidly, suddenly infiltrating every part of the body and mind with an urgent need to be addressed, examined, and understood. Recently I’ve found myself overtaken by an all-consuming fascination with blue, the color of distance.

I’d never been one to look particularly hard at blue when I saw it on clothes, on rugs, on keys or cups or fences or what have you. Blue had always been just blue: the primary color that isn’t red or yellow, our culture’s cue for sad music, melancholy and depressive episodes. There was nothing to be said or thought about the color blue, other than that I knew it was my mom’s favorite color, that I drive a blue car, that blue sometimes looks good on other people, but usually not on me. I prefer wearing black.

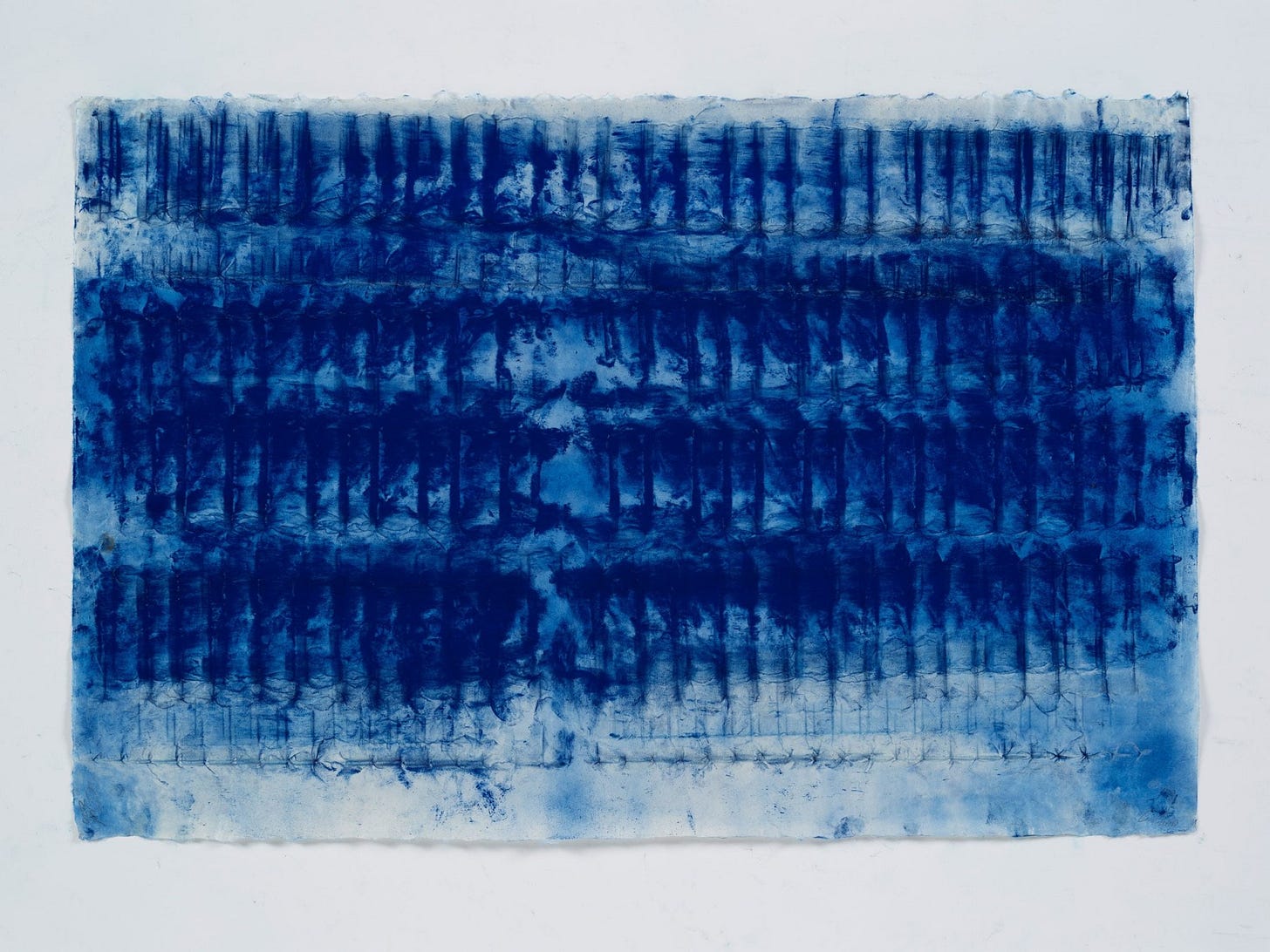

And suddenly, blue was all I could think about. Slowly and somehow violently here I was, manically shucking clothes from the rack at Crossroads in search of the softest, most startling blue cashmere possible; there I was, buying books enrobed in rich blue covers, regardless of their content; here I was, framing a ten-dollar print of Jason Moran’s Bathing the Room with Blues to hang in my apartment; there I was, wondering if it would be too pretentious to walk into my nail salon and ask for a gel manicure and could they possibly do it with a polish as deep and pigmented as Yves Klein’s beloved international blue. Like Moran’s painting, I, too, needed to bathe myself completely in blues.

My sudden fixation wasn’t coincidental, though it was a bit of a delayed reaction. Late last year I read Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide To Getting Lost, a collection of essays exploring the human tendency (and the need) to get lost, whether in cities or wilderness, literally or spiritually. But the book’s opening essay—an examination of the color blue and its relationship to desire, solitude, and distance—was arguably the key that unlocked this new obsession.

It begins like this:

“The world is blue at its edges and in its depths. This blue is the light that got lost. Light at the blue end of the spectrum does not travel the whole distance from the sun to us. It disperses among the molecules of the air, it scatters in water….

For many years, I have been moved by the blue at the far edge of what can be seen, that color of horizons, of remote mountain ranges, of anything far away. The color of that distance is the color of an emotion, the color of solitude and of desire, the color of there seen from here, the color of where you are not. And the color of where you can never go. For the blue is not in the place those miles away at the horizon, but in the atmospheric distance between you and the mountains.”

I’d never considered the color blue to that extent, but the concept of distance felt very familiar.

I’ve always been good at keeping my distance. Solitude is a sacred thing, and the only way to achieve it is to put other people at arm’s length. I live in a tucked-away neighborhood of a decently quiet city on purpose; here, it feels like I’ve succeeded in putting a healthy distance between myself and the chaos of the world, even though all I need to do is walk down a flight of stairs to hit one of Oakland’s busiest streets. I love the company of my friends and family, but I can’t be counted on to show up to every planned gathering, much less to answer a phone call or respond to a text right away—distance makes the heart grow fonder. I have generally always been a little aloof, even to those I’d consider myself very close to. Don’t even get me started on the miles I put between myself and my own goals, because the thing about getting older is that you begin to believe the more distance you put between yourself and what you really want, the less you’ll feel the aftershock when things don’t go your way.

In this sense, distance is treated like a shield: it can save you from getting burned. And if distance is blue the way distance is a protector, it’s no wonder why entire cultures and nations associate blue with protective powers.

Consider the blues characteristic of the architecture across the Mediterranean, Middle East and North Africa. According to traditional Turkish belief, blue repels evil and can absorb negative energy. (See Istanbul’s Blue Mosque and evil eye amulets.) Here in the U.S., porch ceilings in the coastal South are painted with what’s called haint blue, a sky-blue meant to shield homes from wandering spirits. Across the world’s religious artworks, the Virgin Mary—“honored with the title 'Mother of God,' to whose protection the faithful fly in all their dangers and needs”—is almost always depicted wearing some shade of blue. Blue puts distance between you and what is unwanted, troubled, worrisome.

As I plunged into the depths of literature on the color blue, I began to examine to my tendency to hold myself at a distance for protection. I realized that maybe I was playing it a little too safe. What would happen if I worked to allow just a little bit of closeness into my life, to trust blindly that things would be okay without a blue safety blanket to fall back on?

To a certain extent, some levels of distance are necessary to maintain balance in life. But I realized I was using my fallback excuse of a “need for space” to live in complete denial of my desire for the full human experience. It was my balm against the shame of admitting I’m a human with human needs, to let people perceive me and all my humanness close-up. I’d been observing life pass me by from a safe distance.

What I’m saying is that distance can backfire and burn you, too. To live in a constant state of fear of feeling shame and hurt is no kind of life. So, here I am, carefully and intentionally stitching together the wide-open space I’d carved between myself and the life I was afraid of living. I came clean about my feelings to someone I’d held at arm’s length for a long time. I stared down my fear of my own mediocrity and pitched a story to a newspaper (something I’ve wanted to do for years), which I’ll report on soon.1 One of my goals for 2024 is to respond to texts with a little more urgency in an effort to keep the sense of closeness between my friends and family alive. (No matter how much I love spending time alone in my apartment, solitude won’t be what saves me at the end of the day.)

I’m also closing the distance between me and my desire to write fiction. I was recently given the opportunity to participate in a collective flash fiction project with several other writers. (Flash is generally less than 1,000 words, and the goal is to leave the reader with more questions than answers by the end.) The story will hopefully be published in a zine soon. Until then, I’m sharing a a teaser of the story below.

Growing up, Yia Yia told us that blue is the color that wards off evil. It blankets the spirit like a balm. There is blue are blue things everywhere in the house – on coffee cups, kitchen tiles, marble statuettes. They are blue like the color of a new world with no continents, I mean blue blue, staring-into-some-laughing-crevice-of-an-open-grave blue, blue like Yia Yia brushing the knots from my sweat-through, matted hair under the pale glow of a lantern. The big light attracts bugs. In summers we have silverfish creeping into the kitchen corners and I’d hear Sophia beating them senseless with the back of her slipper when we should have been sleeping, undeterred by the swampy indigo of the high July midnight.

Blue like the color of distance. Distance is the coat of armor people wear to protect themselves. There were summers when all of us were pressed together like a cheap deck of cards in the house, Mom and Dad, several aunts, always a baby or two and of course always Yia Yia, all of us stacked on top of each other, so close to suffocation that Sophia and I would run shrieking and panting to the refuge of the orange tree, patron saint of personal space.

Sophia got older, too, quicker than I did, but not old like Yia Yia. Her legs didn’t explode in a tangle of veins, and her hair didn’t turn gray. But her body lengthened and so did her face, each angle of her jawline hardening, the bridge of her nose luxurious, inviting. She kept the delicate ribbon of her pink mouth curled softly at the corners, like she was savoring a misdeed. Summers passed and the curl slowly transformed into a thin line, her brown eyes piercing like a hawk’s under a heavy brow. She spent long afternoons alone underneath the orange tree, baring her teeth wildly if I drew near. Suddenly she felt further away than the orange tree ever had.

Eventually I began to wonder if all the blue in the house had worn off, if perhaps we had expended its reserve of protective power. Did magic have a limit?

One day I asked Sophia if something was chasing her. I sensed there was a murky tension following her through every room. I imagined it must be an evil spirit. It had big bulging eyes and maniacal open jaws, its breath hot on our backs as we sat silently at the table peeling oranges, popping the thick, wet slices one by one into our mouths. This evil spirit was ripping the closeness of childhood apart, replacing it with the somber separation that adults carve senselessly between each other, the blue of distance. She didn’t answer.

Blue is the color of the light that gets lost, and I don’t want to lose my light just yet.

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you in May!

Big thanks to Kate for getting me in touch with the editor. :)