Fear Is Out In 2024

On bell hooks' love ethics, Mary Ruefle, Rilkean angels, and sponsored ads for Lexapro

I’ve spent the last few weeks of 2023 staring at my Google calendar and wondering how the hell the year managed to slip away from me so quickly. I’m sure many of you can relate. More importantly, I have also been plotting, scheming, and planning how to ensure the new year begins on the right foot. I’m thinking about the energy I’d like to carry into 2024 with me, as well as what I should let go of.

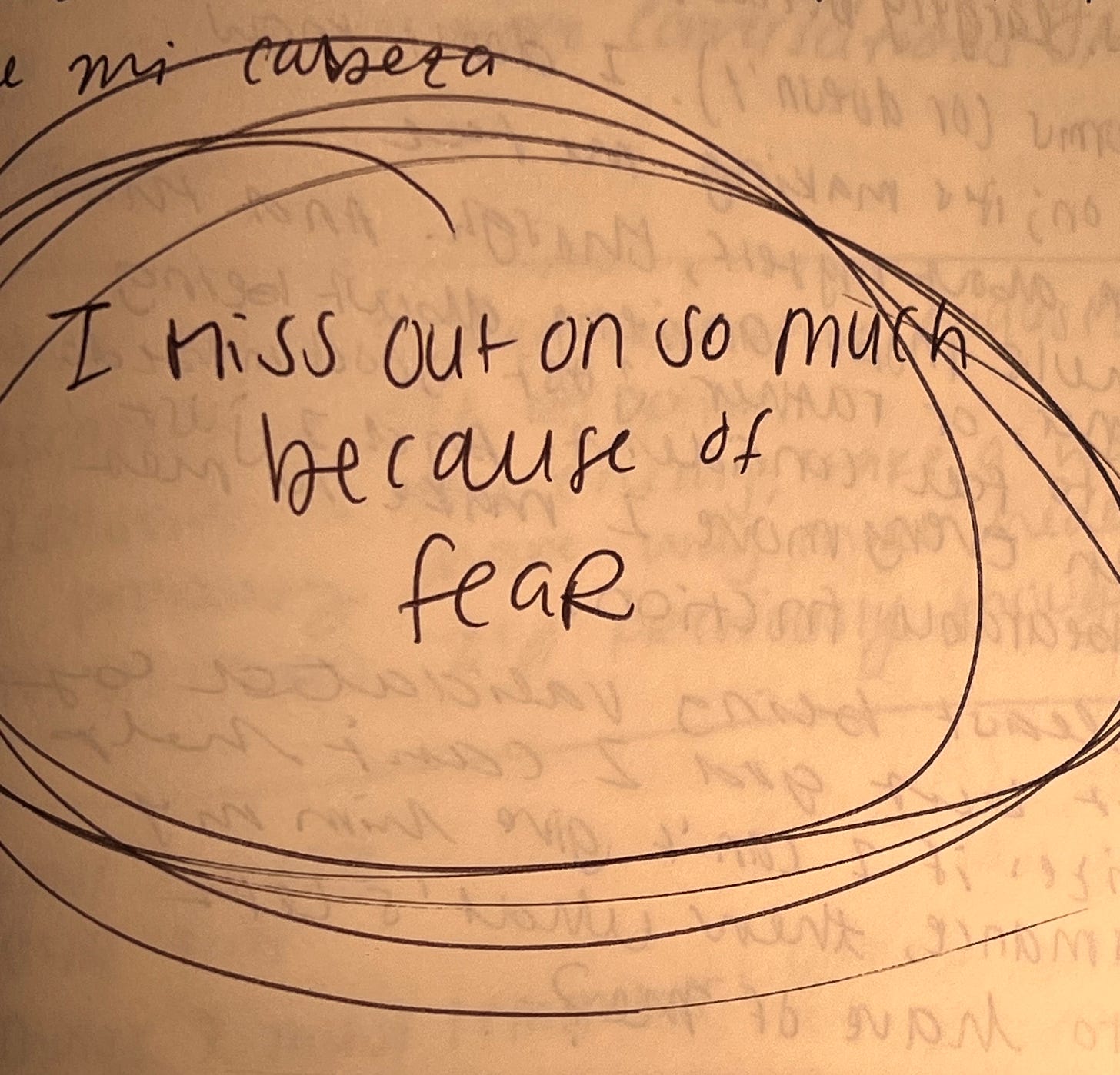

Regarding what no longer serves me, what comes to mind is fear, the world’s greatest motivator. I stole that denotation from Mary Ruefle’s 2012 lecture On Fear, which I will reference here frequently.

I’d been mulling around the idea of fear long before the end of the year, and long before I stumbled across Ruefle’s lecture last month, but the fear of my entire writing career being a waste was keeping me from getting up and writing the essay to begin with. So, as much as this piece is intended to be a critical examination of fear—what it is and what it means—it also serves as a bird-flipping to the very concept itself, because, after all, fear is nothing if not useless and temporary, and there’s no use dragging this ball and chain with me into 2024.

But the truth is I am terrified almost every day regardless. This is possibly because I’m getting older, and also because I have rampant anxiety that is unquestionably fueled by a boundless caffeine addiction. I’ve never gotten an official anxiety diagnosis, but I have gotten sponsored ads for Lexapro on Instagram, so. There’s that.

Anxiety is often intellectualized as a fear of the future, which checks out. The future is a hazy, far-off place that contains both certainties and uncertainties, both of which can induce real panic if you think too long and hard about them. For instance: It is certain that one day I’ll die. It is uncertain how, when, and in what bodily and cognitive condition. Spooky!

What I’ve come to realize, though, is that I don’t necessarily fear specific outcomes. It is not death itself I am afraid of; it is dying, the act of, the verb, never the noun—the process of succumbing, not the state of not being (or, perhaps, of being something other than human, something unknown). I think this sentiment is shared by many. And if you believe, as my Opa would say, “es kommt alles was kommen soll,” loosely translated to “everything that is destined to happen will,” then you might feel relative comfort in knowing that no amount of anxiety can change the future.

Es kommt alles was kommen soll—that’s not what scares me. Instead, it’s the riptide of emotions I’ll drag myself into in the aftermath of (or perhaps the duration of) any predetermined, “scary” occurrence. In essence, I fear myself.

Could the fear of oneself be anxiety’s engine? Perhaps the brain fears the monster it has created and subsequently unleashed, the one now running rampant through your own skull, clacking its teeth and spitting venom at you whenever you are called to battle life’s uncomfortable truths. When Mary Ruefle was writing her essay on fear, she called a philosopher friend to mull over the subject with. He told her that “fear is to recognize ourselves.”

I think the word “recognize” is powerful here. To recognize is to acknowledge the existence of something. Acknowledging your own existence is to accept your wholeness, the entirety of your being—including the ugly stuff, not just the parts you prune to present to other people. And to recognize that you are, in fact, an imperfect person, possibly one who is capable of doing and feeling horrible things, is terrifying.

Let me tell you what I mean.

Like most people, I fear abandonment. However, the actual act of someone disappearing from my life—while it is certainly always painful—is not an outcome I regularly dread. People come and go and they will continue to do so through my lifetime: this is a fact I can accept.

What I dread most is the anticipation of what I will feel after the abandonment occurs. I fear the fury, the lies I will tell myself (“you deserved it,” etc.), the disbelief, the heartbreak that will follow. In other words, I am terrified of the unleashing of parts of myself I don’t want to face.

If you grew up in California then you know that it’s not the earthquake itself we should be wary of, but the aftershock. The danger of tsunamis lies not within the first wave, but in the crushing walls of water that relentlessly pummel the shoreline. An initial action begets a consequence, the latter of which is often far more deadly than the action itself.

Patriarchy would tell me that fearing the wrath of my own emotional state is a sign of weakness, that “the degree of fearfulness is one measure of intelligence,” as Nietzsche argued. But in this vein, anxiety is possibly more than just the recognition of oneself. Perhaps it’s also a sick type of self-reverence.

There are many cultures worldwide that worship what they fear, and that which they fear is often invisible, the way emotions are. Consider the folks who describe themselves as “God-fearing Christians.” When Rainer Maria Rilke first perceived an invisible angel appear to him on the walls of the Duino castle1, its divine beauty terrified him. Whether the fearsome entity be a deity or your own brain, to fear something is to admit it has power over you.

Will I continue to run from this power or will I turn to face and fully embrace it in 2024? After devouring All About Love by bell hooks earlier this month, I want to firmly believe it will be the latter.

I picked up the book with teeth stained plum red after wobbling out of my favorite wine bar a few Saturdays ago. The wine had me ruminating over a lot of emotional blockages I’d self-inflicted over the last year. I wanted to unplug them to cultivate a healthier emotional state in 2024. This book seemed like the perfect remedy. And, surprise—after hungrily plowing through it, I was finally able to admit that fear was the root of so many of those emotional blocks.

Mary Ruefle: “Fear is desire’s dark dress, its doppelgänger.”

bell hooks: “Fear stands in the way of love. When we take to heart the biblical insistence that there is no fear in love, we understand the necessity of choosing courageous thought and action. This scripture encourages us to find comfort in knowing that ‘perfect love casts out fear.’ . . . . As one gives and receives love, fear is let go.”

When I finished All About Love I thought that perhaps the antidote to my own anxiety is not Lexapro, but a generous helping of self-love, as well as the willingness to extend love to others.2 After all, if I can fear the power of my own shadows, I should be able to worship them, too. And to worship means to sit with, commune with, embrace, and love all of me, not just the good parts. If “fear is to recognize ourselves,” what is loving ourselves, then? It’s to recognize and accept ourselves in every state of our being. Cutting myself off from my intrinsic emotional being, desires, and goals—just because I’m afraid of confronting my darker sides—is out in 2024.

Embracing a love ethic, according to bell hooks, is what empowers us to transcend that fear and live our lives as they are meant to be lived. It took me a long time to write this essay because I was afraid it wouldn’t make much sense, or worse, that it would be mediocre. I was afraid that I would simply be parroting the works of authors who are much greater artists than I am. In fact I am shaking in my boots every time I hit publish on this damn app. But my life is supposed to be lived as a writer, and writers need to hit publish, despite what their fear might tell them. I wrote about my tendency to avoid difficult tasks and emotions in October; this I’ll leave behind in 2023 as well.

Surrendering to a love ethic is both beautiful and terrifying, like the Rilkean angel. But I have a good feeling about 2024. Until then, I’ll be plotting what to write about come January—fearlessly and with fervor.

See you next year!

Suggested reading:

On Fear by Mary Ruefle

All About Love by bell hooks

The First Elegy of the Duino Elegies by Rainer Maria Rilke

Rainer Maria Rilke resided at Duino castle, the home of his close friend Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis, between the fall of 1911 to the spring of 1912. There, walking along the castle property, he believed to be confronted by an angel, which prompted him to write some of his most important poetic work, the Duino Elegies.

Don’t be silly, if you have spoken to a health professional who has deemed Lexapro or other drugs fit for your anxiety then please take them. You can’t self-love your way out of everything.