In Defense of Silence

On whale infravoices, Spotify wrapped, social media, and Ilya Kaminsky's "Deaf Republic"

Being on social media these days means being subject to a lot of noise. For the most part, this noise is mind-numbing, brainless chatter designed to distract, rake at your deepest insecurities, and convince you to make decisions marketers want you to think you came up with on your own.

I am unfortunately on social media all the time because I am addicted to it. I haven’t figured out how to quit cold turkey yet. This means I spend a lot of time thinking about noise and, more recently, silence: its elusive, luxurious counterpart.

Silence is an interesting concept because its reputation ultimately depends on its context, both culturally and circumstantially.

There are some cultures that deem silence as an almost inalienable human right. Consider the designated “silent cars” in the trains slicing across the German countryside, for example, as well as the passive-aggressive notes anyone who’s had the misfortune of living with German neighbors has inevitably had tacked onto their front door demanding Ruhe (silence).

But jump south to Colombia and you’ll quickly find that the concept of silence bears no significant weight there whatsoever. It’s not that quiet is impossible to find there—silence just isn’t culturally held to the same degree of importance. One year I stayed in Medellin for three months and nearly institutionalized myself; the constant barrage of (admittedly beautiful, but very loud) salsa music at all hours, coupled with the sound of vendors howling and traffic snarling from the street, was contributing to a severe lack of sleep and making me insane.

In the U.S., silence is a bit of a double-edged sword. It’s appropriate in certain contexts (at funerals, in libraries, et. cetera), but it can be deemed rude, entitled, or awkward in others.1

At this point in my life, I think it’s safe to say I’ve mastered the art of carving awkward silences into conversations. This is fine with me because others tend to fill that silence for me regardless. Leveraging awkward silence as a tool in conversation is something I picked up in journalism school, because the secret to a good interview is to lean into the silence until the interview subject breaks it, even to the point of the exchange becoming unbearably uncomfortable.

People panic when they sense a lull in conversation. They start chattering to fill that space. This is usually when the gold nuggets of conversation begin to surface in the pan. Raw vulnerability emerges when you’ve run out of the pleasantries, when you’re left only with the meat and potatoes of the matter. But beyond that, it’s really that cultural considerations tell us it’s better to say something at all than to sit there in tortured silence.

Why? Despite this trick being exceptionally useful in conversation, I want to push back on the idea that silence is something to be filled, like it’s some kind of meaningless, purposeless void.

Given the humanitarian atrocities occurring in the Middle East I have turned (again, always) to poetry, and specifically to Ilya Kaminsky’s collection of narrative wartime poems, Deaf Republic. I think about what he wrote in the end notes:

“The deaf don’t believe in silence. Silence is the invention of the hearing.”

Silence is often believed to signify the absence of something, but, like Kaminsky said, this is the invention of the hearing. Did you know that until 1967, the ocean was widely accepted as completely silent, devoid of any sound at all? We are a self-absorbed species. It wasn’t until the Navy plunged sonar into Bermudan waters to spy on Russian submarines that they discovered that humpback whales were sending eerie, mournful melodies to each other through the depths. Later still, the discovery of frequencies beyond human sensorial range—like the infrasound of blue whales—would prompt a reexamination of our core belief that silence must be devoid of anything.

We take silence to mean emptiness, when in fact the silence can hold something as powerful and haunting as the song of a whale, the clicks and whirs and moans of a leviathan mammal, our distant relative. But I don’t need to get into the poetics of whale songs to make my point. How much do you think exists solely within the silence between humans?

I can think of the many messages I have left unanswered, and of messages I have sent that were never dignified with a response. The silence of those cut-off correspondences carry the weight of a thousand possible outcomes, of relationships ended. They also carry the mixture of lingering anger, of wounds still tender, of chapters closing. I wonder what Kaminsky would think about our tendency to describe silence as “deafening.”

I think about potential (again, a word that comes up frequently in my essays) and how silence is its bearer. How much potential for clear thought and healthy communication is webbed within the fibers of a heavy silence? When I read How To Do Nothing by Jenny Odell this summer, one line in particular—a passage from Gilles Deleuze’s Negotiations—stood out to me.

“Repressive forces don’t stop people expressing themselves but rather force them to express themselves; what a relief to have nothing to say, the right to say nothing, because only then is there a chance of framing the rare, and even rarer, thing that might be worth saying.”

The potential for clarity of thought—for peace, perhaps—exists in silence, but repressive forces demand we speak. This is interesting when I think about it in the context of social media, where we are constantly cajoled to like, share, hit subscribe, share our thoughts, tag your friends in the comments section. Instagram, Twitter, and every other platform out there demand from us endless noise, and to what end? And the passage becomes even more interesting when revisiting the premise of Deaf Republic:

Deaf Republic opens in an occupied country in a time of political unrest. When soldiers breaking up a protest kill a deaf boy, Petya, the gunshot becomes the last thing the citizens hear—all have gone deaf, and their dissent becomes coordinated by sign language. The story follows the private lives of townspeople encircled by public violence: a newly married couple, Alfonso and Sonya, expecting a child; the brash Momma Galya, instigating the insurgency from her puppet theater; and Galya’s girls, heroically teaching signs by day and by night luring soldiers one by one to their deaths behind the curtain. At once a love story, an elegy, and an urgent plea—Ilya Kaminsky’s long-awaited Deaf Republic confronts our time’s vicious atrocities and our collective silence in the face of them.

What can we learn about silence wielded as a tool, a resource for resistance and personal resilience? How much are we giving up by constantly filling silence with the noise of, could we say, an oppressor? What happens when we stop to listen, even when we believe there’s nothing to be listened to?

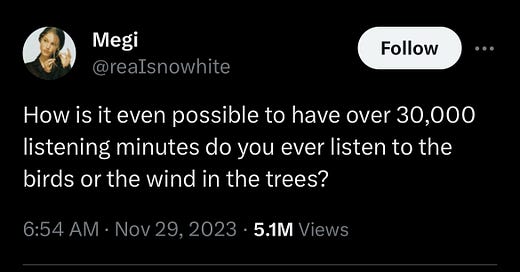

Spotify Wrapped dropped yesterday and, to my own surprise, told me that I’d clocked a whopping 95,905 minutes of listening this year. That amounts to 66 days straight of listening. (And that’s not even including what I will listen to in December.)

Music is evidently important to me, but I had to pause and ask myself: Why did I spend my year trying (and succeeding) to deafen myself to the silence around me? How many opportunities to learn from silence must I have missed in that time totaling 66 consecutive days?

In the approximately three-ish hours it’s taken me to write this essay, I’ve forced myself to plow ahead without headphones on. I generally listen to melodic techno or something similar while writing. But in the absence of music, I’ve found the presence of clear thought, undistracted writing, and, surprisingly, pleasure. Writing has been a bit like pulling teeth lately, but today, I’ve found my flow state. I hope you invite the stillness in and find the same.

Suggested reading:

Deaf Republic, Ilya Kaminsky

Silent Whale Letters, Ella Finer and Vibeke Mascini

How To Do Nothing, Jenny Odell

Suggested viewing:

What are you listening to? by __we_love_you_ on IG

Of course, that’s true in places like Germany and Colombia, too, because nothing is black and white. But I wanted to use those as examples of two countries that place a fundamentally different value on silence.